Sugar cane chaff, the byproduct of an important Latin American export cash crop

After the 1970s it appeared that Panama was taking a step in the right direction to becoming a fully independent state, most notably by arranging the transfer of the Canal ownership to Panama. However, from the 1980s on Panama has yet to break itself free from external influence. Its economy can be greatly affected by whether or not the U.S. has decided to give it aid. Additionally, U.S. forces were necessary to remove Noriega from power when he had gotten completely out of Panama's government control. Currently, Panama is progressing towards more industrialization and tourism rather than its prior subsistence style living. This shift places an even greater importance on foreign countries due to Panama’s reliance on foreigners visiting and spending money, and also relying on the importation of more goods as it reduces the amount of staple goods produced. Today, Panama's economy relies primarily on the service sector, accounting for 80 percent of the GDP. This sector mainly consists of the Canal, banking, commerce, and tourism, all of which heavily depend on the international market.

U.S. Aid[]

During the rule of Omar Torrijos in the 1970s, United States aid to Panama had been generous, based on the good relations between Torrijos and the United States government. Indeed much of Torrijos' populist appeal as a caudillo stemmed from social programs funded in part from U.S. aid. After the death of Torrijos U.S. aid dropped to far less than previous years with only $2 million towards development and $300,000 for military assistance. Not until 1985 did the United States aid once again increase, showing that the Panamanian government was once again in favor with the United States, through close ties between the CIA and the Panamanian military working towards stopping drug trafficking (Conniff 148).

Much speculation has arisen in the last year in regards to current president Ricardo Martinelli’s rightwing government and its support for increased U.S. involvement. Panama announced in early November, 2009, that four aerial-maritime bases were scheduled for construction as a means to combat rampant drug trafficking, a priority that helped earn Martinelli his presidency in 2009. Although the government stresses the endeavor as an “entirely Panamanian initiative”, Martinelli’s recent visit with U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton over bilateral anti-drug efforts and deputy interior minister, Alejandro Garuz’s September comments about the “international cooperation agreement” regarding the construction of two naval bases has left many Panamanians both confused and concerned (Latin American Weekly Report, 2009).

The fact that U.S. financial aid is such a big deal in Panama and has a large impact on their economics supports the fact that Panama is dependent upon the United States to a certain degree. With such large amounts of money given to Panama the United States is furthering the dependency of Panama instead of allowing the country to stand on its own.

Corruption in the Government - The Torrijos-Noriega Regime[]

The Torrijos-Noriega regime, 1968 to 1989, is a period in Panamanian history marked by corruption in the government. Both Omar Torrijos Herrera and Manuel Antonio Noriega were on the payrolls of the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) during this time. Their involvement in United States’ intelligence services led, in part, to the corruption of the Panamanian government. Evidence incriminating these two leaders was largely ignored because the U.S. government perceived their value as U.S. informants as more important than their crimes. Prior to the1977 Canal Treaties, the desire to settle a new canal treaty also caused the United States to disregard the criminal activities of the Torrijos administration. Soon after Torrijos came to power he was supported by the U.S. because he “was definitely more amenable to negotiate a new Canal treaty” (Murillo 88).

Since the removal of Noriega from power in Operation Just Cause countless cases of drug trafficking and money laundering involving top Panamanian officials of this era have surfaced. The chief assistant US Attorney General for the District of South Florida stated in 1988 with reference to Noriega that “There’s absolutely no question that, through all the administrations since 1969, we had more than adequate information that this guy was a dope dealer and chose to ignore it” (Murillo 232). On February 21, 1978 a censored Intelligence Committee report stated that, “Some sources have provided intelligence which we view as reliable and which we believe suggests that Gen. Torrijos know about narcotics trafficking by government officials” and that “several drug dealers have alleged that they were friends of Gen. Torrijos, that he was one of their customers, or that he protected them” (Murillo 237).

The corruption of the government during this period was not limited to drug trafficking and money laundering. Although there multiple accounts of torture and murder have been uncovered two of the most public were the murders of Father Héctor Gallego and Hugo Spadafora. Father Gallego became a nuisance to the families, relatives of Torrijos, which controlled the economy of the Santa Fé, a small rural town where he was stationed, when he began working to help the peasants improve their financial situation. To help his relatives regain economic control of Santa Fé, Torrijos had Noriega beat and kill Father Gallego (Murillo 117).

Hugo Spadafora was a popular physician who had participated in the Sandinista revolution of 1979. When Spadafora spoke out against the Noriega regime in the 1980s, the dictator had him brutally murdered in September of 1985. When details of the murder became public and President Nicky Barletta ordered an investigation, Noriega dismissed Barletta and alienated himself from the international community (Conniff, 2001).

Operation Just Cause[]

In December of 1989 the United States made a strategic military decision to invade Panama in an attempt to remove General Noriega from power; the invasion was formally known as Operation Just Cause. Other disputably justifiable reasons for the invasion include drug trafficking suspicions and to protect the human rights of Panamanian citizens as well as Americans living in the Canal Zone. The death tolls and impact on Panamanian civilians remain uncertain, however the United States succeeded in removing Noriega from power. This invasion leads to questions of dependency, as the Panamanian government was corrupt and uncontrolled by the country as a whole and outside forces were necessary to remove a dictator from power.

Additionally, the harsh economic measures implemented by the United States against Panama in an attempt to force Noriega out of power sent the country into a severe economic depression. This, in combination with the bloodshed of the invasion, left Panama reeling and more dependent on U.S. aid than ever before (Rudolph 148).

Tourism[]

Tourism is fairly new in Panama and heavily complicates the issue of dependency within the country. Though tourism is a means of income for many industrialized nations, the presence of tourism in Panama, before economic independence has been fully achieved, may lead to a prolonged dependence rather than economic gain. In recent years this movement towards tourism has expanded nationwide, especially in the area of ecotourism. Many areas such as El Valle, Boquete, and much of Bocas del Toro now rely on tourism as one of their main sources of income.

Tourism in these areas and elsewhere in the country has provided many new jobs, directly and indirectly encouraging the creation and expansion of business in specific areas with the infusion of capital. The problem with Panama's expansion of tourism is that a good deal of the businesses profiting from the industry, such as hotels, are foreign owned, so wealth has continued to be extracted from this nation. Even on the lower scale, many workers in hostels, hotels, tourist attractions, even b

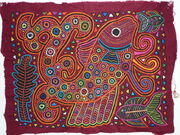

A Kuna mola that caters to tourists by depicting an underwater scene rather than more traditional geometric designs

ars and restaurants and are not citizens of the country, as is evident in Bocas del Torro. Clearly, although the increase in tourism is providing an influx of commerce, the positive impacts of that increase are not solely directed towards Panamanians. Similar to the arrival of migrant Caribbean and American workers on the canal, tourism seems to be providing an ample supply of jobs to foreign English-speakers, which may pose the same problem of unemployment that arose after the completion of the canal.

An exception to the trend of outside ownership is seen with the Kuna Yala, a comarca where foreign owned businesses has been avoided thanks to the Kuna's insistence of absolute autonomy of thier lands. The Kuna are an indigenous group that resides on the Carribean coast on a series of islands. The Kuna take great pride in their culture and have only been able to maintain their traditions so well by enforcing stricts limits on tourism within their land. However, they are also at risk of having an economic break down because of their reliance of outside commerce, rather than having a self-sufficient economy.

Export Economy[]

In 1978 the transisthmian oil pipeline was constructed. By 1981 the pipeline had paid for itself. In 1983 the pipeline added $154 million in revenue to the economy (Zimbalist and Weeks, 1991). This made the pipeline responsible for 3.5% of Panama's GDP. This is a further example of Panamas decision to base its economy on transit services.

The export of goods, particularly agricultural products increased during the 1980's (Zimbalist and Weeks, 1991). Small farms tend to produce staple crops whereas large farms produced crops for export such as bananas and sugar. So when small farms decreased and large farms increased in the 1980's the export of crops increased as well. However, since small farms decreased so too did the amount of staple crops. This forced Panama to increase the import of staples from other countries.

Today agriculture in Panama continues to remain divided between subsistence farming and commercial farming for export. According to the latest World Bank survey agriculture makes up about 7% of the country’s GDP and employs 15% of the active population (“Panama: Economic”). The main export crops are bananas and all other fruits, corn, sugar, rice, coffee, shrimp, construction wood, vegetables, and livestock (“Panama: Economic”). The exportation of bananas is reminiscent of the banana republic that engulfed much of Panama and other Central American countries. The biggest exporter in Panama of bananas today is the Chiriqui Land Company (producers of the brand Chiquita), a subsidiary of United Brands which was formerly known as the United Fruit Company ("Agriculture") .

The collapse of the Las Perlas fishing industry is one example of the volatility and difficulty of managing an export-driven economy. During the 1980s, fishermen flocked to the Las Perlas archipelago on the Panamanian Pacific coast in hopes of cashing in on the bountiful scallop harvest. At $6.30/kilogram, scallop meat provided a much more generous income to native Panamanians than most other occupations allowed. At its height, the fishery created 35,000 new jobs; however, lack of government regulation soon led to overexploitation. By 1991, scallop harvests dropped below profitable levels, and the industry virtually disappeared (Medina et al, 2007). The Las Perlas fishery is just one example of how unpredictable and transient export driven economies are; as a result, their development is unlikely to pull Panama from the throes of foreign dependency.

Studies in economic dependency have shown a positive relationship between increased international integration and “national disintegration”, a term referring to the level of inequality in a nation’s wealth distribution (Ray & Webster, 1978). Skewed distributions are amplified when underdeveloped nations either deal with one or a few nations, or have only limited commodities to trade. Assessing economic prosperity through GNP or GDP alone is a highly ineffective measure of a nation's overall wellbeing. The 1980's were typically viewed as a prosperous time in Panamas economic history, but the fact remains that some people's prosperity does not equate to everyone elses. In fact, in the 1980's Panama had a very unequal distribution of funds. The richest 20% had twenty-three times more money than the poorest 20% (Zimbalist and Weeks, 1991). The unequal distribution of wealth and the increased import of staple crops further increased Panamas dependency to other countries since the people were now forced to buy their food and had less money and land to produce their own.

Industrial Development[]

Although Panama has attempted to expand its economy beyond that of an export-driven system, its efforts have been met with limited success. Early Panamanian industry, such as the Santa Rosa Sugar Refinery near Aguadulce, sought to produce goods from raw materials extracted domestically. Industry expanded rapidly from 1950 to 1970 due in large part to new restrictions on foreign goods in the Canal Zone, which allowed local industries to grow and become more competitive (Conniff, 2001). Although import substitution industrialization in the 60s and 70s allowed for the expansion of some sectors of the Panamanian economy, the small domestic market and relatively high labor costs hindered growth in manufacturing. Public projects took the lead, with the government building cement plants, metal works, and sugar refineries. Despite this, industrial job creation in Panama has lagged behind the growth in the labor force during the 1970s and 80s (Meditz and Hanratty, 1987)

Sugar cane enter the Santa Rosa Sugar Refinery.

One area of the industrial market that has shown promise for Panama is energy. Numerous oil refineries have been built over the last three decades, especially in Colon, a major industrial center in Panama. The construction of hydroelectric dams, such as the Edwin Fabregas Dam on the Rio Chiriqui at Fortuna in 1984, has provided a sustainable source of electricity and jobs. During the 1980s, hydroelectric power accounted for 10% of the nation’s electricity consumption (Meditz and Hanratty, 1987).